| Dimitrije

Buzarovski Teaching Music Composition in the 21st Century: The Kingdom of Loops* |

|

– teaching

creativity – selecting among

different genres (contemporary, classical, jazz,

rock, pop etc.) – selecting

between classical tonal tradition and other

contemporary approaches. We

will leave all these dilemmas for another

occasion, and concentrate only on

the

influence of the specific phenomenon which

appeared at the beginning of the 1990s and became

typical for music creation in the new century – the loops. There

were two parallel lines which contributed to the

appearance of loops – sequences and

samples. The

sequences were introduced

to music hardware and software through the MIDI protocol in the

mid 80s. The basic music principle (and of

course not only in music) of

repetition

was implemented in the philosophy of the new

computer software, and soon, at the end of the

80s, MIDI sequencers where graphically developed

from matrix to score

presentations.

The MIDI protocol is still the basis of score

processors, in fact it is their essential and an

integrate part, and despite of the fact that

MIDI technology is already

very

outdated, i.e. too slow for the capacity of the

computer hardware, the world still operates with

the old rules fixed in the mid 80s. Its

interchange ability and general use enabled it to

survive much longer than the use of any other

protocol.

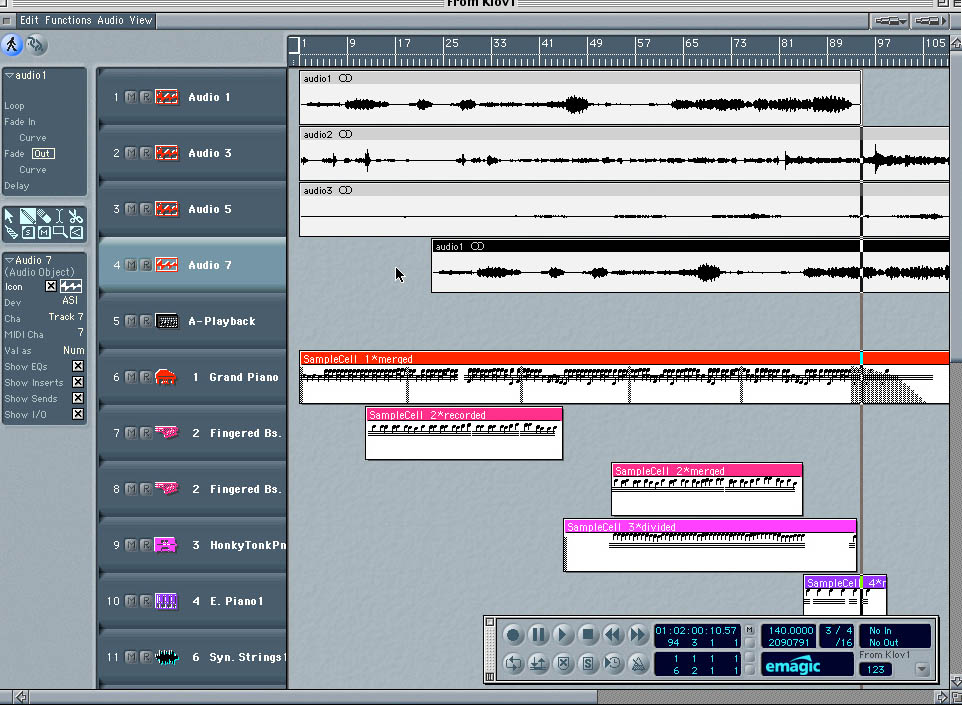

At

the beginning of the 90s, the first commercial

HD audio recording hardware

and

software (such as DigiDesign Pro Tools)

integrated the sequencing principles.

Based

on

the MIDI sequencing principle, the recording

process was built around audio sequencer, again

presented through the timeline of the recorded

music piece.

It

was already predictable that at the next stage,

(when the capacity of the

hardware

will be able to handle video), the sequencing

principle will be extended to the video area.

Today, all video recording software uses

sequencing with separate or

integrated

audio sequencers. Furthermore, most of the audio

recording software, in addition to

having audio and MIDI sequences, also have the

capacity to drive video

sequences.

Once

the sequencing principle was established, the

loops appeared. They were

treated

either as an indefinite repetition of a

sequence, or a part of a sequence (a sequence within a

sequence). In fact, there is almost no

difference between a sequence and a loop, as sequence

could be defined as a loop which appears once or

several times, while the concept of a

loop always includes at least one repetition.

Today, we are inclined to think

of a

sequence almost as something identical to the

music piece, forgetting that the basic idea behind

sequencing was to integrate several sequences

into a piece. Thus, the loops

are

something smaller than a sequence. The

first MIDI sequencers were used to drive sounds

from different sources – analogue or

digital. Digital sound sources were based on

another important principle – sampling.

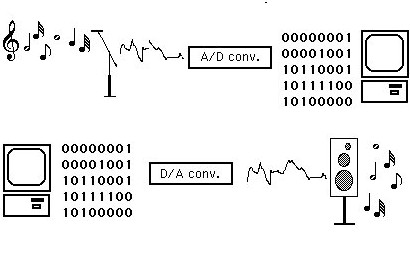

Audio

sampling, which is in fact the conversion of the

analogue into a digital

signal,

had to deal with the problem of loops. In order

to build indefinite sound sustainability

without clicking between the repetitions of the

original short sample, once

again,

the loops were introduced. The limited capacity

of the commercial music hardware at the end of

the 80s and the beginning of the 90s could not

compute larger algorhythms,

not

to mention the building of an instrument, which

needed a matrix of overlayers of

samples

in differenet registers, techniques of

performance etc. The

first samples used in the new audio digital

technology were mainly the

recordings

of acoustic instruments, thus helping the

synthesizers to produce bigger variety of

sounds. Very soon, the expansion of the capacity

of the hardware brought

about

the first longer samples, i.e. the samples with

longer duration, which consisted of the combination

of more sounds (such as tympani or cymbal

tremollo). On

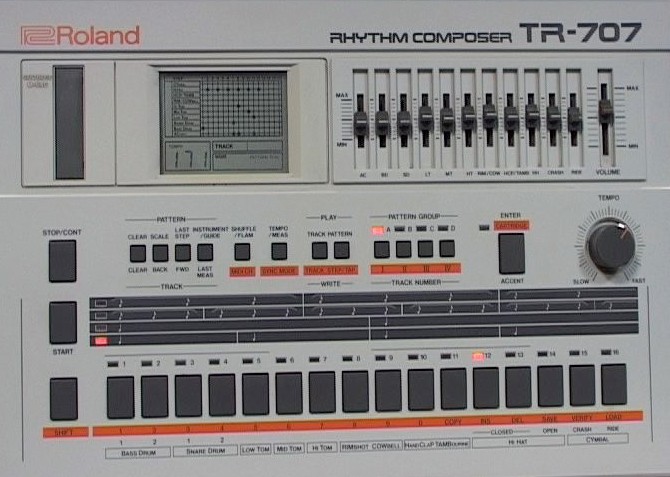

the other hand, the rhythm machines from the 80s

had already employied a combination of the MIDI

sequencing and loops with prerecorded samples of

percussion. At that moment it was very easy to

predict where technology was heading.

The

first concerns were raised from the copyright

societies, as it was obvious that

a

significant parts of the compositions could be

built by the use of the loops. The main question was

whether the rights should be partly distributed

to the factory which

prerecorded

the patterns and samples. The

further development of the digital audio

technology conritubuted to the

greater

expansion of the variety of loops, which

included more and more different sounds, and

later the possibility of transposing or changing

the duration of the loops from

real

sounds (transposition and tempo changes were

available at the very beginning of the use of MIDI

instruments). In

the mid 90s, I was often approached by the users

of this technology who have

very

limited, or in some cases no music education,

but who were creating music by combining

different loops of prerecorded sounds. At that

moment, it was perfectly clear

that

this was a challenge for the traditional way of

creating, and consequently teaching music. In the foundation of this creation

lay the «collage» technique,

which was not unknown and was

particularly developed with the musique

concrète in the 50s. The concept was

entirely the same only the founders of the genre

Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre

Henry

did not have the advantage of DSP editing or

transformation of sounds. Meanwhile,

the kingdom of loops grew with accelerating

speed. With it grew the

number

of its users, especially in the area where it

started - rhythm (machines). This resulted in the

creation of an entirely new music practice of

the late 20th and early 21st

century

– the DJ. The

D(isk) J(ockey)s were the first to grasp the new

technology in structuring a

full

event. Their main task

(music for dancing) brings the rhythm in the

foreground – and loops originate

from rhythm. «Dancing is a rhythm» –

and the loops offered a lot of

rhythm

which could be controlled. Using loops as a

basis enables unlimited prolongation of dancing, thus

surpassing the problem of the duration of songs.

Although at the

beginning

DJs were not interested in fixing their work in

sound carriers, as the main purpose was the

live event, we can already find CDs with DJ

music. The

use of loops in some of the genres dominating

the last decade of globalized

music,

such as techno, rap, hip hop etc., was probably

an interaction. Loops were particularly

useful for the permanent repetitions in these

genres, very easy to create, and

in

general they form a very high percentage of the

music material (even in some techno pieces, all of

it). The adding principle of building the

compositions in these genres (the

piece

usually starts with a rhythmic pattern with a

percussion or bass section, and then new elements

(patterns, loops) are added one by one, or

subsequently), contributed to the

use

of loops. Loops and the structure of the music

pieces of these genres interacted in their

development, thus further widening the

kingdom

of loops. And

here we are today, with loops everywhere, from

electronic music to all kinds

of

rock, pop, techno, hip hop, ambient, DJ music

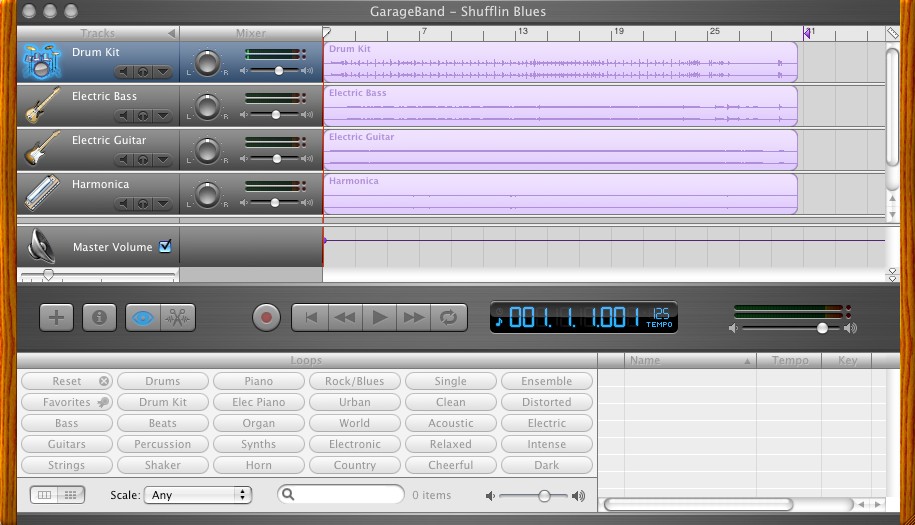

etc. The software

industry closely

followed

and responded to this trend. The latest packages

with the Macintosh operative systems (OS X –

panther, tiger etc.) include a free software for

audio and MIDI recording

– Garage

Band.

Although

with a much lower performance compared to the

similar professional

packages

and mainly targeting the wide audience of music

fans, this software is in fact at the level of the

professional HD audio and midi recording from

the beginning of the 90s.

It

also reflects our dreams of getting rid of all

additional hardware (cards, interfaces etc.) which we needed

in the 90s. It was evident that the rise of

hardware computing capacity

would

result in software solutions. The fascinating

side of this development is that today, we could even

process video without additional hardware (Final

Cut for instance). Video needs much more

computing power, communication capacity and

storage space, than the

audio

itself. Garage

Band comes with a set of hundreds of loops even

categorized in different

genres

(for instance Rock/Blues). The availability of

loops is further extened by Internet exchange. There

are thousands of loops which can be imported

from the Internet. The integrated MIDI

instruments in the system software (Quick Time

instruments) enable

interventions

inside the loops, including the change of tempo

or transposition. Music pieces could be

created faster than their full length

(duration), something unthinkable in the past. The

integrated mikes in the latest models of Mac

computers, add to the karaoke

fun

of creating music. We

should not underestimate the value of the

thousands of pieces created by

amateurs

with these new tools. Some of the compositions I

have heard, made by enthusiasts,

have a much higher level of creation than a lot

of electronic music pieces

from

the 60s to the 80s. In some cases, electronic

music from the past looks naïve when compared to the

achievements of the loops collage. We

can expect that this development will be

accelerated to the extent where we

will

question the need of new recordings, as there

will be enough recorded material to build any kind

of music composition. If in the 90s music fans

who did not have music

education

could create music by buying synthesizers,

rhythm machines and other modules, nowadays,

everyone has access to music tools by bying Mac

computers. How

does this relate to teaching music composition? In

a certain way music composition has always taken

advantage of collage for

building

the overall structure of the piece. Considering

the philosophy of computer editing and its

three crucial commands copy/cut/paste

there

are more than obvious

similiarities.

The first score processors equally introduced

the principle of loops by copying, cutting

and pasting the repetitions of the same thematic

materials, and even

whole

sections. New horizons were opened up for the

faster creation and assembling of the music piece. Consequently,

we can not say that the loops principle is not

already integrated in

the

composition courses, and students of

composition, especially those who are more inclined to

follow the development of technology, are fully

aware of these advantages.

The

question is how professional composers will

compete with the army of enthusiasts and amateurs

making music while playing with their computers,

and how does music

education

fit into this picture? Some

of the answers lie in the history of electronic

music. We can find a lot of

engineers

without elaborate music education, from Leon

Theremin to Max Mathews. Bringing our

arguments to the utmost limits, we could expand

this concept to the link

between

music and mathematics from the Pythagoreans to

Iannis Xenakis. Nevertheless,

the sole tools were insufficient for creating

music which would

surpass

the local geographical and historical

boundaries. Loops tools are undoubtedly the most developed

in the history of music civilization, offering

half-processed products to

the

users. But

there was always one feature which immediately

distinguished the trained

musicians

from the auto-didacts: the possibility of

creating larger music forms. In fact, at the moment there

are almost no large compositions (both in the

sense of the form, and consequently in

the duration) in all other genres except in

classical music. Even the

largest

compositions in the popular genres – the musicals,

are only a collage of smaller

fragments.

We are not taking into consideration the DJ

creations where the duration is controlled by

the dancing pattern. Popular

20th century music genres, including jazz, rock,

techno, etc., passed the

history

of western classical music in a condensed form,

from the purely vocal tradition, to separate vocal

and instrumental idioms (17th c.). The

development of the music forms was directly

influenced by the development of instrumental

music and particularly

orchestras. In

this sense, large forms can not be built simply

by collaging the loops. In most

of

the music which was presented to me by these

enthusiasts, I could immediately notice their inability

to develop the patterns into an integrated

composition. Unfortunately, their talent and

intuition could assist them in only creating

small fragments. That is why we

have

never heard a larger form than a song even from

the greatest musicians of the 20th century popular

genres. Music

forms are only one of the manifold aspects

determining the artistic (or

artisan)

capacity of the contemporary composer. We did

not mention all the other disciplines for

fear of digressing from the main topic of this

paper. During the last 27

centuries,

being one of the first disciplines in the

history of human civilization (both scientific and

artistic, once again thinking of the

Pythagoreans), music, in comparison to all other arts,

developed the highest level of specialization in

the area of technical knowledge and

skills. However, knowledge of tools is only a

prerequisite and not a

guarantee

for the artistic and creative results. On the

other hand, we can assert that without

appropriate knowledge and skills, we can not

expect results which will survive

the

sharp blade of historical selection. All sound

compositions sound, but only some

are

music. There

is no doubt that the inevitable kingdom of loops

will be adequately

integrated

in the composition curricula. Pierre Schaeffer

and Pierre Henry could be proud of their

invention – we are enjoying

the results.

↑ Back to top |

| Home |

© Buzarovski, 2018

All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication of any of the materials related to the files which are part of this web site is a violation of applicable laws. |